Berkeley’s Top Cop Michael K. Meehan Outpacing ‘Media Curve,’ Reaches Out to Berkeley ‘Daily.’

by Steed Dropout

June, 19, 2012

CHOCOLATE WITH THE CHIEF

I arrived early, and began casing the joint, Au Coquelet, a 35-year Berkeley coffee house/restaurant/meetup, steering clear of the fishbowl plate-glass window I envisioned collapsing in a fusillade of hit-men’s bullets.

Au Coquelet derives from Middle English — small cock.

I was awaiting the arrival of Chief Michael K. Meehan and a newly promoted captain, Andy Greenwood, and feeling small. I’m also old.

The chief and his beleaguered-by-the-press captain wanted to get to know me better, the chief said. Was I being investigated, or just being checked out for sanity, or manipulative possibilities, or as we say here in Berkeley just being “played?”

Why now? I have written many pieces on Berkeley P.D., not all of them favorable, and in the course of chocolate with the chief (he doesn’t drink coffee, even though he served 23 years with the coffee-sated Seattle P.D.) I expressed remorse for my police “sex-scandal,” yarn, a self-serving piece that was too cheap a shot for other bay area reporters, who nevertheless have teed off on the chief for weeks.

My sex-scandal cheap-shot was written, in desperation, to bring me to the attention of police, whom I blamed for not returning my calls. I had to read about our police in the Chronicle or East-Bay majors.

I also wanted to impress my editor at the Berkeley Daily Planet, who recently editorialized, “It’s been very hard, verging on impossible, for reporters to pry information out of the BPD in the 10 years I’ve been watching them regularly….”

“We tried many different kinds of people on the police beat in the 8 years the Planet was in print-young, old, experienced, naïve, stern, charming-the whole gamut. Nothing ever really worked, and no other publication has done much better.”

I identified myself in my editor’s remarks, as both old and charming. Still, the BPD media spokeswoman had never returned one of my calls, although I have been on speaking terms with the chief and the captain, both of whom have said they read me.

I once told Capt. Greenwood, “it’s so good to be read by cops.”

“I read you as a human being,” he said. Berkeley police have been pushing the “we’re human beings” angle.

That did not keep me from applying pressure on BPD when it seemed, in February, they might have prevented a murder in the hills.

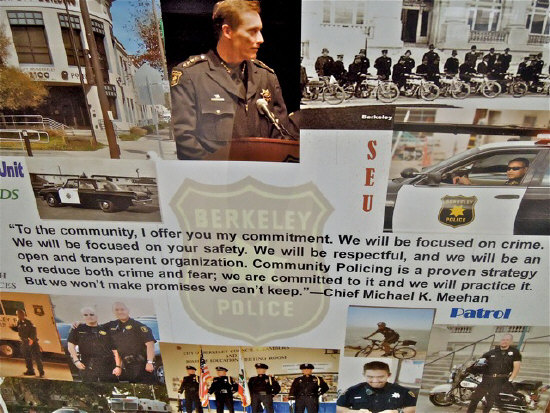

Northbrae Community Church, February, as Chief, top right, stages media event to address public safety concerns after murder in hills, some felt could have been prevented. Police beats commander, left, a dispatcher supervisor, middle. Reporter, who got all the publicity by being 'visited,' later by a police media spokeswoman, shown with raised camera, right, middle.

Northbrae Community Church, February, as Chief, top right, stages media event to address public safety concerns after murder in hills, some felt could have been prevented. Police beats commander, left, a dispatcher supervisor, middle. Reporter, who got all the publicity by being 'visited,' later by a police media spokeswoman, shown with raised camera, right, middle.CORRECT THIS AND OTHER ERRORS

in response to intense media-heat over the February murder of a well-known Berkeley scientist in the exclusive Park Hills neighborhood, the chief put together a public info extravaganza with police spokesmen from different divisions taking Berkeleyans behind the scenes with dispatchers and beat supervisors.

Audience jeers turned to cheers as the presentation stretched to midnight. Then the chief stumbled into destiny, dragging a bay-area reporter (not me, dammit) with him. Surely you read or heard about it — the incident went viral, after news that the chief had sent his armed media spokesperson to the home of the reporter, whose story the chief felt needed correcting.

I agreed with the chief’s correction to the other guy’s story, even as I wrote that I was jealous of the reporter who got the media spokesperson’s visit, when she never answered my calls or emails. I was this close to my big Sunset Boulevard scene. I could see it in the camera of my mind, the sergeant looking very fishy through the small security lens of my apartment door.

But alas and alak.

My jealousy was only worsened by the fact that the media spokeswoman’s press releases (breaking crime stories) in my paper often led my own. Then, I tried to sneak up on the sergeant at the station house. After waiting around an hour, I penned the following note.

Capt. Greenwood reminded me that the department still has the note. The note: : “I’m here to offer my support [which will be taken as bullshit] for the department. And by the way, you can come up to my apartment anytime. Be sure to bring the gun.”

I might have said worse, like, “be sure to bring the gun…THAT’S SO HOT!”

Everyone got the joke, but I did some nervous pacing over my thoughtless act. My recklessness helped me understand the chief’s situation, and the situation of all, who err. As Alexander Pope wrote — “to err is human, to forgive, divine.”

Just when I thought I’d never hear from the police again, I got a Saturday morning call from the chief, correcting an egregious error I’d committed in a piece about him. The chief’s correction, while too late to make me famous, did get me to write a piece on corrections, which I hope will be read.

The mistake is really a whopper. I quote directly: “…without qualification or attribution, that Police Chief Michael K. (or is it M.?) Meehan now speaks only through an attorney. I learned of my mistake from the chief, who spoke to me directly and without an attorney.”

“I think he said, he didn’t even have an attorney, but am not sure. His departmental spokesperson has an attorney, but she won’t talk about it, with or without an attorney, but she may wish to correct me on that,” I wrote, still sniggering over my malfeasance.

But I later corrected a whopper error in a story on teen gangs downtown.

Is there anyone out there who would read a column, not just corrections, about corrections?

WHAT YOU TALK ABOUT OVER CHOCOLATE WITH COPS

If you’ve read A.W. Parker’s narrative account of the formation of the Berkeley police, and its beloved turn-of-the century “kid constable,” August Vollmer, you might lead with that since the chief often mentions Vollmer, whose name is still revered in Berkeley.

You might mention that the book was published in your hometown, Springfield, Il., by Charles Thomas, who published your high school newspaper out of a now-famous Frank-Loyd Wright house.

The chief might tell of his trip to Springfield’s Lincoln shrines with his wife and kids four years ago.

You might mention, you grew up a few blocks from lincoln’s home and hung-out there in the summers watching tourists gawking at Abe’s out-house.

When I wasn’t talking about myself, I asked the two police executives how they had become cops. Greenwood, a Berkeley boy, had decided to become a cop in high school, often riding along with one of his mentors. The chief was working as a restaurant manager when he got the call, much the way clergymen do, after his mother died, and he wanted to do, he said, more with his life.

You might offer public relations advice to the chief, even though you know damn good and well that he would never be advised from outside the department. You might try to pry loose a copy of the top-secret city-manager’s $50,000 report on the chief’s handling of media. You and the chief might agree to disagree over PR.

You would like to tell the swells who did the report on the chief, that when it comes to press relations, the chief was doing a pretty good job with you. He paid for my hot chocolate.

You want to do a piece putting the chief out front on crime-fighting in Berkeley, but you learn that the chief doesn’t want to call attention to himself. You have concluded that chiefs like to be judged on their accomplishments, and crime stats are down in Berkeley.

The chief gives you contact info on criminologists the chief listens to.

You wouldn’t leave without relating your first Berkeley bust, in 1970, running a red-light on a Schwinn. “They had to have five cars.”

“Why so many cars,” the chief asked. “I was turning blue with anger,” I fessed up,(“when we mess up, we fess up,” the chief likes to say) and besides, an officer said I was being “obstreperous,” a word, and the officer’s choice, I have remembered forty years.

“Obstreperous,” the chief smiled, stumbling over the word. I have stumbled over it myself. I re-iterated how impressed I had been by the word choice.

We spent the rest of our well over an hour fat-chew discussing crime film comedies, bonding over that sub-genre of crime films. “Can I watch Hollywood Homicide,” with the kids? the Chief wondered.

I didn’t want to make a mistake. “It has sex in it,” I recalled.

I saw the chief at a rowdy council meeting. He was too tired to speak, he said, but had noticed my use of the word “obstreperous,” in a recent headline. He stumbled on the word, and we had a good laugh. I recently wrote the chief and his captain: “it’s great having friends who would give up their lives to protect yours.”